- India

- International

Archaeological Survey of India will ‘delist’ some ‘lost’ monuments. What’s happening, and why?

Some of India’s protected monuments, part of the country’s rich historical heritage, have disappeared — they have been lost to development, encroachment, or neglect. Which monuments are these, and when did the ASI find out?

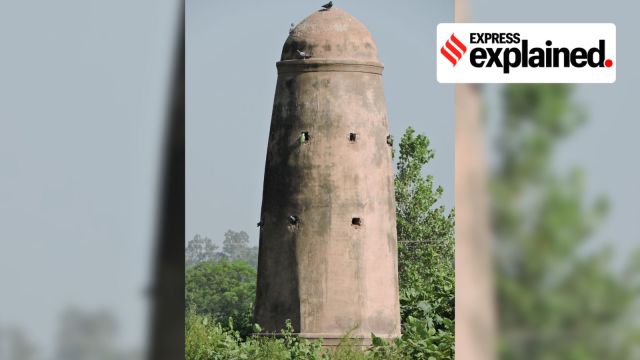

A Kos Minar in India. These were milestones during the Mughal era. One such Kos Minar in Haryana is in the ASI's list of 'missing' monuments. (Via Wikimedia Commons)

A Kos Minar in India. These were milestones during the Mughal era. One such Kos Minar in Haryana is in the ASI's list of 'missing' monuments. (Via Wikimedia Commons)The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) has decided to delist 18 “centrally protected monuments” because it has assessed that they do not have national importance. These 18 monuments are part of an earlier list of monuments that the ASI had said were “untraceable”.

Among the monuments that face delisting now are a medieval highway milestone recorded as Kos Minar No.13 at Mujessar village in Haryana, Barakhamba Cemetery in Delhi, Gunner Burkill’s tomb in Jhansi district, a cemetery at Gaughat in Lucknow, and the Telia Nala Buddhist ruins in Varanasi. The precise location of these monuments, or their current physical state, is not known.

So what exactly does the “delisting” of monuments mean?

The ASI, which works under the Union Ministry of Culture, is responsible for protecting and maintaining certain specific monuments and archaeological sites that have been declared to be of national importance under the relevant provisions of The Ancient Monuments Preservation Act, 1904 and The Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, 1958 (AMASR Act).

Delisting of a monument effectively means it will no longer be conserved, protected, and maintained by the ASI. Under the AMASR Act, any kind of construction-related activity is not allowed around a protected site. Once the monument is delisted, activities related to construction and urbanisation in the area can be carried out in a regular manner.

The list of protected monuments can grow longer or shorter with new listings and delistings. ASI currently has 3,693 monuments under its purview, which will fall to 3,675 once the current delisting exercise is completed in the next few weeks. This is the first such large-scale delisting exercise in several decades.

Section 35 of the AMASR Act says that “If the Central Government is of opinion that any ancient and historical monument or archaeological site and remains declared to be of national importance…has ceased to be of national importance, it may, by notification in the Official Gazette, declare that the ancient and historical monument or archaeological site and remains, as the case may be, has ceased to be of national importance for the purposes of [the AMASR] Act.

The gazette notification for the 18 monuments in question was issued on March 8. There is a two-month window for the public to send in “objections or suggestions”.

And what does it mean when the ASI says a monument is “untraceable”?

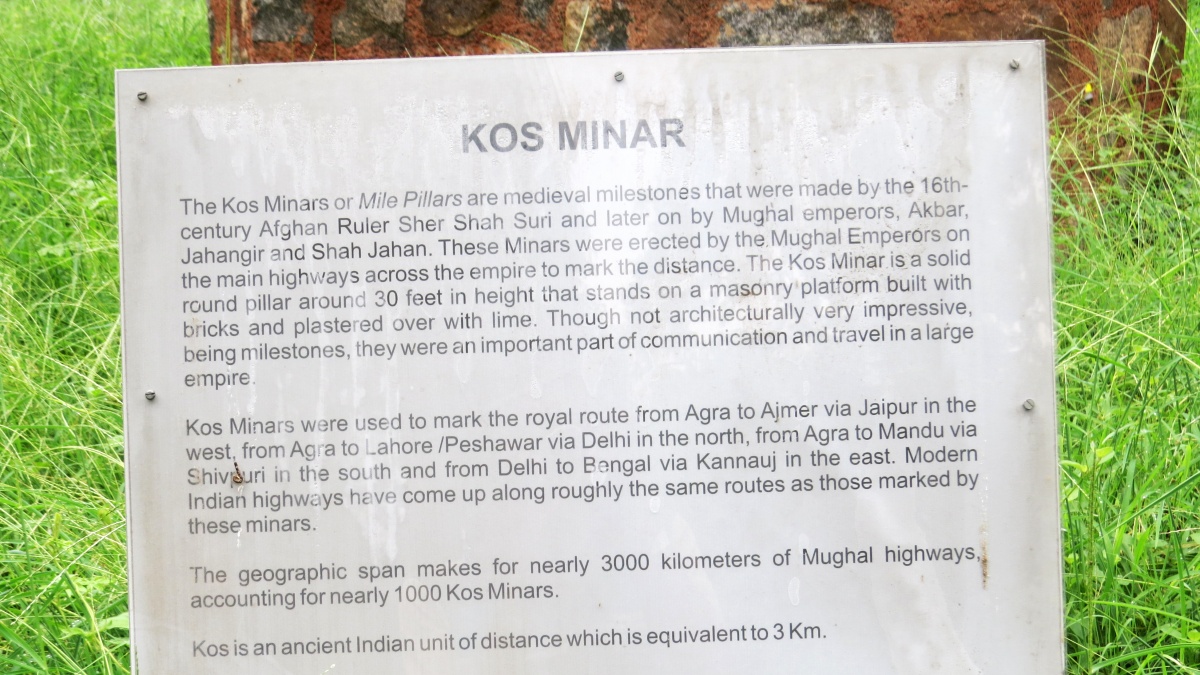

The AMASR Act protects monuments and sites that are more than 100 years old, including temples, cemeteries, inscriptions, tombs, forts, palaces, step-wells, rock-cut caves, and even objects like cannons and mile pillars (“kos minars”) that may be of historical significance.

A board on Kos Minars at the Delhi Zoo. (Via Wikimedia Commons)

A board on Kos Minars at the Delhi Zoo. (Via Wikimedia Commons)

These sites are scattered across the length and breadth of the country and, over the decades, some, especially the smaller or lesser known ones, have been lost to activities such as urbanisation, encroachments, the construction of dams and reservoirs, or sheer neglect, which has resulted in their falling apart. In some cases, there is no surviving public memory of these monuments, making it difficult to ascertain their physical location.

Under the AMASR Act, the ASI should regularly inspect protected monuments to assess their condition, and to conserve and preserve them. In cases of encroachment, the ASI can file a police complaint, issue a show-cause notice for the removal of the encroachment, and communicate to the local administration the need for demolition of encroachments.

This, however, has not happened with uniform effectiveness. The ASI, which was founded in 1861 after the need for a permanent body to oversee archaeological excavations and conservation was realised, remained largely dysfunctional in the decades that followed.

The bulk of the currently protected monuments were taken under the ASI’s wings from the 1920s to the 1950s, but in the decades after Independence, the government chose to spend its meagre resources more on health, education, and infrastructure, rather than focusing on protecting heritage, officials said. The ASI also concentrated more on uncovering new monuments and sites, instead of conserving and protecting existing ones.

How many historical monuments have been lost in this way?

In December 2022, the Ministry of Culture submitted to the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Transport, Tourism and Culture, that 50 of India’s 3,693 centrally protected monuments were missing. Fourteen of these monuments had been lost to rapid urbanisation, 12 were submerged by reservoirs/ dams, and the remaining 24 were untraceable, the Ministry told the Committee.

The Committee was informed that security guards were posted at only 248 of the 3,693 protected monuments. In its report on ‘Issues relating to Untraceable Monuments and Protection of Monuments in India’, the Committee “noted with dismay that out of the total requirement of 7,000 personnel for the protection of monuments, the government could provide only 2,578 security personnel at 248 locations due to budgetary constraints”.

The Parliamentary panel said it was perturbed to find that the Barakhamba Cemetery in the very heart of Delhi was among the untraceable monuments. “If even monuments in the Capital cannot be maintained properly, it does not bode well for monuments in remote places in the country,” it said.

Officials had told The Indian Express at the time that the cemetery may have been lost to the “redevelopment of the New Delhi Railway Station”. The cemetery is now set for delisting.

Was 2022 the first time that the disappearance of these monuments was noticed?

ASI officials had told The Indian Express then that no comprehensive physical survey of all monuments had ever been conducted after Independence. However, in 2013, a report by the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India had said that at least 92 centrally protected monuments across the country had gone missing.

The CAG report said that the ASI did not have reliable information on the exact number of monuments under its protection. It recommended that periodic inspection of each protected monument be carried out by a suitably ranked officer. The Culture ministry accepted the proposal.

The Parliamentary panel noted that “out of the 92 monuments declared as missing by the CAG, 42 have been identified due to efforts made by the ASI”. Of the remaining 50, 26 were accounted for, as mentioned earlier, while the other 24 remained untraceable.

The Ministry said, “Such monuments which could not be traced on ground for a considerable time because of multiple factors, despite the strenuous efforts of ASI through its field offices, were referred as Untraceable monuments.”

Eleven of these monuments are in Uttar Pradesh, two each in Delhi and Haryana, and others in states like Assam, West Bengal, Arunachal Pradesh, and Uttarakhand. An official had told The Indian Express at the time the Parliamentary panel’s report came out that, “Many such cases pertain to inscriptions, batteries and tablets, which don’t have a fixed address. They could have been moved or damaged and it may be difficult to locate them.”

This is an edited and updated version of an explainer that was first published in 2023.

More Explained

EXPRESS OPINION

May 03: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05