Deep beneath the Earth’s surface, there’s a gigantic cache of diamonds, according to new research. While it’s unlikely that we’ll ever be able to obtain these diamonds, knowing that they’re there helps us learn more about our own planet and what it’s made of.

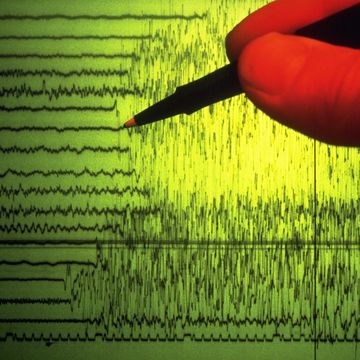

To discover what lies beneath the surface, scientists can’t simply look with their eyes. Instead, they use sound waves and listen. Unlike light, sound can travel through solid rock, and by listening closely scientists can learn a great deal about what the inside of the Earth is like.

Typically, these sounds come from earthquakes or volcanic explosions, and by studying the resulting seismic waves scientists can determine what materials lie underground. One group of scientists was studying a strange anomaly that occurs when these seismic waves pass through underground structures called cratonic roots. These structures are ancient, highly dense rock formations shaped like inverted mountains that lie hundreds of miles beneath most tectonic plates.

Because these rock formations are so dense, sound waves move much faster through thes cratonic roots than through most other rock. But for some reason, many of the seismic waves measured over the last few decades move even faster than predicted. A group of scientists, led by MIT scientist Ulrich Faul, suspected that some material inside the cratonic roots was speeding up these waves.

To figure out what exactly these roots were made of, the researchers created a series of computer simulations using hypothetical rocks made of different materials. Of all the different simulations they tested, the only one that agreed with the data was a simulation where the cratonic roots were made of about one to two percent diamond, in addition to ordinary rock.

This discovery is a big deal because cratonic roots make up a significant fraction of our planet’s crust. If even two percent of these structures are made of diamond, that equals quadrillions of tons of the mineral buried under the surface. Unfortunately, cratonic roots are located around a hundred miles underground, so mining expeditions seem unlikely.

"This shows that diamond is not perhaps this exotic mineral, but on the [geological] scale of things, it's relatively common," said Faul. "We can't get at them, but still, there is much more diamond there than we have ever thought before."

Source: MIT